News Publishing

Lost in Subscription

30 years ago, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the introduction of the World Wide Web changed our world forever. While most media industries have successfully transformed their businesses into digital services, many news outlets are struggling. What happened in this transformational process? And where did publishers go astray?

Do you remember the time when we used to actually own things?

I’m not talking about cars or real estate. I mean regular, day-to-day stuff. Like music, for example. “True Blue” by Madonna, the first CD I ever owned, cost US$30. I listened to it until my ears bled, because back when I was a teenager, 30 bucks was a hell of a lot of money and I couldn’t afford to buy another CD for months. This was the late 80s, when Germany was still divided in two parts – the capitalist West and the communist East.

Ten years later, Germany was reunited, the Soviet Union had ceased to exist and I remember buying my first DVD. In fact, I made the switch from VHS to DVD just because of this one title: “The Matrix,” a movie that would have been a disgrace to watch in any other format but digital. The DVD cost nearly US$40. A smart investment, I thought, fantasizing that I would one day watch that digital video disc with my grandchildren. Ha!

Physical media just doesn’t seem to make much sense any more in this digital Matrix that we have ourselves transcended to.

Last weekend, almost 20 years later, I cleaned out my attic. A whole box of CDs and DVDs went to the landfill, including Madonna’s “True Blue” and “The Matrix.” The original plan was to selling my vintage music and movie collection on eBay, but after one look at the listings I realized it was just not worth my time. Even despite the few pennies I would have collected, sending out physical media just doesn’t seem to make much sense any more in this digital Matrix that we have ourselves transcended to.

Moving from Possession to Subscriptions

For years now, I have had several digital subscriptions, including Spotify and Netflix. I don’t own that stuff any longer, but I can listen to as many Madonna songs as I want, wherever I want. The Matrix trilogy is currently part of the Amazon Prime catalog and therefore free to watch. So is “Good Bye, Lenin,” one of my favorite German comedies (yes, you did read that correctly – German and comedy). I can’t help but smile about how the roles have changed – the communists have turned into hardcore capitalists, while we, the capitalists, have given up on the idea of possessing or owning stuff. That certainly wasn’t what Marx and Lenin had in mind, but it’s still fascinating.

Over the years, our lives have moved from ownership to subscriptions. We don’t pay to possess content, but to use it. This cultural shift has had a huge impact on any number of industries, businesses and services – especially the media. When I consider my personal expenses for media services, I have seen tremendous changes over the years. Most of my TV show, movie, software and even (audio) book consumption has shifted to monthly subscriptions. With the introduction of Apple Arcade, Apple TV Plus, Disney Plus, Quibi – and who knows what else, by the end of 2020 – I might have signed up for a dozen media services.

*

*

No Subscription for News

There is, however, one subscription that I had for most of my adult life that I no longer require: a newspaper subscription. Due to high entry prices and the lack of single article purchases, I don’t spend any money on journalistic content at all. Somewhere during the transformation process from the analog to the digital world, publishers lost me.

It seems I am not alone – hardly any of my friends have a news subscription either. And I am not talking about old school door-delivered newspapers. I am talking about subscriptions for journalistic content in general, digital or otherwise.

I ask myself: Where did we, the news media, screw up? Where did we get lost in digitalization?

Why is it that people would rather consider signing up for a fight club, than feed their brains with high quality journalism? As a journalist myself, whose existence depends on people paying for news, I ask myself: where did we, the news media, screw up? Where did we get lost in digitalization?

For nearly a decade I’ve been studying the developments in the market. I’ve had numerous talks with experts at conferences. I’ve worked with promising media start-ups such as LaterPay to help develop new means of payment in the digital sphere. But most of all, I talk and listen to ordinary people outside of my own media bubble and I keep asking why they don’t pay for journalism any more.

There is, of course, not just a single cause that explains the growing disconnect between news media and the people formerly known as their audience. But I think I have identified three major areas where media and news-consumers seem to have parted ways. Please consider the following to be a conversation starter only – if you’d like to contact me directly, I’d be thrilled to discuss my conclusions further.

*

*

1. Content

The most striking area I think is the content itself. We all crave smart analysis, thought provoking editorials, and carefully selected text. But let’s be honest here for a second: most content that the news media produces is flat, boring copy-and-paste newswire journalism.

I remember once talking to a data analyst, who helped organize the first online-campaign for President Obama. After he was done explaining the technical details of his work, he concluded: “But most of all – with Barack Obama we had a great product to sell!”

(At this point, one could argue: “Okay, but how did we end up with Donald Trump then?” Here’s the thing: he is a great product. I would even argue, in the digital era, that Trump is an even better product than his predecessor. Why? Because he is anything but mediocre. Fun fact: since Trump has been in office, subscriptions for the New York Times and the Washington Post have both surged).

If there is one thing that I’ve learned in the digital market, it is that nobody is willing to pay for mediocracy – not with their attention and certainly not with their money. That’s why Netflix is investing billions of dollars in high quality TV shows. That’s why Whole Foods can charge you crazy amounts of money for their vegan gluten-free Kombucha. And we certainly don’t need to discuss Starbucks, do we?

*

*

2. Pricing

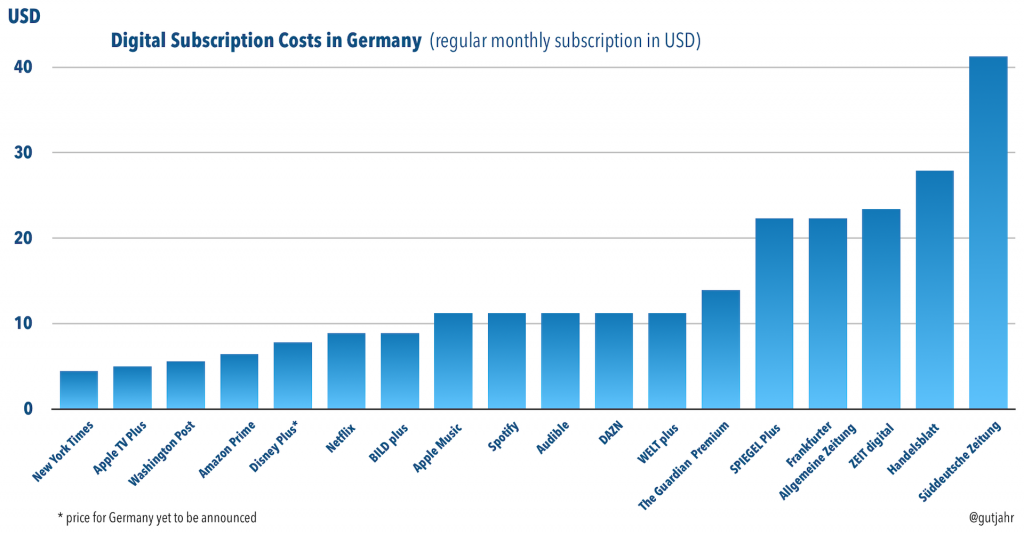

We also need to talk about pricing. Take a look at the graph above that shows the monthly subscription costs for digital media in Germany. Most European publishers (except Springer) try to charge almost the same prices as if the Internet had never been invented. I once talked to a high-ranking manager at Der Spiegel in Hamburg. He argued that publishers were not willing to accept subscription fees below €20 a month (the same as the original print subscription).

The idea that it is for the publishers to define what people should consider a fair price proves a deeper lack of understanding of the problem. Given that the customer is always right, let’s have a look through the eyes of a consumer, living in a digitalized world, shall we?

When it comes to entertainment, you can get a complete library of all the music that has ever been published. You can get a catalog of movies and TV shows that would have easily outnumbered the VHS-stock of any Blockbuster rental store. And you get all this at a flat rate of 10 bucks a month – for content that you won’t just consume once, but will watch and listen to over and over again, even sharing it with your entire family.

In the news world you get a product that is limited to the library of one single publisher, sometimes even just to one title. You get news content that is largely available everywhere else for free. Content that you consume only once and that is already outdated within the next day or two. And for that you’re asked to pay twice or three times the amount of all the Disney, Marvel, Pixar and Star Wars movies ever made?

Remember the words of Tim ‘Apple’ Cook at the latest Apple event, promoting Apple TV Plus on stage: “All of these incredible shows for the price of a single movie rental. This is crazy.” I would argue, no, it is not crazy. It is not even that smart. In today’s media reality, it is the necessary thing to do. Trying to charge more than 10 bucks for a subscription in a globally digitalized world – that is what I consider to be crazy.

*

*

3. Accessibility

Recently I was at Starbucks waiting in line. While I was surfing the web, I stumbled upon an article at Der Spiegel that seemed to look promising. The text was behind a paywall, so I decided to sign up for a test subscription. Although there were several people standing before me, I wasn’t able to unlock the text before it was my turn to place my order.

By the time I got my coffee, I was so frustrated filling out the subscription form that I completely forgot about the article. The window of opportunity to sell me a subscription had closed. Life went on, but the frustration stayed. The likelihood I will give it another try some day is correspondingly lower.

Think about it: we media people wasted nearly two decades complaining about and fighting Google. We called our very own customers names – thieves or parasites, who refused to pay for our journalism, while we forgot to build digital cash registers that were suitable to fit our needs in these increasingly faster and mobile times.

For years our readers were not used to paying for journalism online at all. We even coined a word for this kind of phenomenon in the German language: “Gratiskultur,” the expectation that all journalism on the Internet is free. That was an attitude that we created, by neglecting the needs of our audiences. WE did that! We taught the people not to pay us. We trained them.

And while we are finally beginning to do the obvious, to make the checkout process faster so that our readers are finally at least technically able to sign up for our products while standing in line, companies such as Starbucks, McDonalds or Amazon are getting rid of waiting lines entirely by providing their customers with even faster, frictionless digital payment solutions.

*

Conclusion

With the advent of the Internet, people have so many choices, on- and offline, that they can no longer afford to waste their limited (and therefore even more precious) time and money on mediocre products. That’s why I’m so annoyed by publishers complaining that users are not willing to pay for journalism.

- People are willing to pay for all sorts of digital content (oh boy, do they pay!), but not for mediocracy, especially not for products that are lacking heart, soul and depth. No more.

- With the growing number of subscriptions, it is crucial to keep subscription prices in line with the market reality, not to our own needs or desires. If that means subsidizing subscriptions for a couple of years, then so be it.

- The competition is no longer limited to our own line of profession. As more businesses move into the subscription arena, our competitors will soon be BMW, Pfizer and The Dollar Shave Club.

- We need to deploy seamless, easy-to-use solutions for people to pay for our content or services. Surprisingly, signing up and paying for news content still takes longer than standing in line at Starbucks.

As we move deeper into the subscription economy, with half of the world’s population now having access to the Internet, I see great opportunities for digital journalism to thrive.

But before we go all crazy about subscriptions, we should be aware that there is only so much money people can spend every month. The Reuters Institute for Journalism has detected a “subscription fatigue,” where people are getting tired of being asked to pay for so many different subscriptions. I think we need to offer easier ways to let readers pay for their daily news, beyond monthly subscription plans.

I also think we need new forms of collaboration amongst publishers in order to offer one joint catalog of journalistic content beyond our own newspaper brand or outlet. A monthly all-you-can-read flat rate for all the titles that are not the New York Times or the Washington Post. It’s time for Apple News without the Apple. A bundle of great journalism for the price of a coffee.

Impossible? Maybe. But remember when we spent a fortune on our CD and DVD collections? As we move into the next chapter of our digital future we need to think the impossible. Or as Morpheus said: “You have to let it all go, Neo. Fear, doubt and disbelief. Free your mind.”

***

Thank you for this analysis.

May I add “diversity” as an aspect between the non-mediocre and the price tag reasons?

Living between countries and cultures, I see the importance of different viewpoints quite clearly. The truth is mostly somewhere in between.

So a for me attractive subscription “bundle” would combine different publications.

I don’t want to wake the old terms of “coopetition” and “syndication” but would such a combination of viewpoints not be appealing to the audience out there?

News outlets have their special style of writing and like everywhere else, likeminded people tend to work together. That gives each publication a certain tendency and a likeminded audience.To see beyond, I would appreciate a real combined offer.

Btw. about current streaming services I dislike the most, that I need at least two subscriptions to get the offer which I would like to use.

Just some thoughts for the night …

Richard, thanks a lot for your valuable research and analysis of the economics of media. I have nothing to add to the notion of subscriptions. But I came across an article about the EU ePrivacy Regulation and the latest adjustments to the draft by the Finnish presidency (in German): https://www.heise.de/newsticker/meldung/E-Privacy-Verordnung-EU-Ratsspitze-wil-breiten-Zugriff-auf-Nutzerdaten-erlauben-4591769.html

I wonder if the right to track for media websites might mean the media industry could go on with the „Gratiskultur“ and stay financed by the advertising industry. But I also wonder if a right to track can legally be limited to one industry – even if it is a very valuable industry. And most of all I wonder which websites and apps will call themselves a provider of content which is eligible to the right to track.

If you have any though on this matter I am curious to read.